By Alex Fink, CEO @otherweb.com

Can AI Fix the News?

Let’s leave no sacred cow unslaughtered and find out.

When it comes to The News, people tend to fall into one of 3 categories:

1. The Chomskiites who think it was always bad.

2. The Ostriches who think it was (and still is) just fine.

3. The Chicken Littles who think it used to be ok, but now the sky is falling.

Now, here’s the problem. Nobody likes Chicken Littles. They’ve predicted 9 of the last 0 apocalypses. But I submit to you that this time – and perhaps only this time – they are actually right.

Hear me out.

Newspapers first appeared in North America in the 1700s, and for the first 200 years they were primarily an intra-party affair. Subscriptions cost a fortune, and most people could not afford one. The target audience was educated elites and party loyalists, and the content was partisan advocacy at its best:

● The New-England Courant was published by Benjamin Franklin and advocated against British rule.

● The Boston Newsletter was subsidized by the British government and advocated for it.

● The New York Post (yes, that New York Post) was founded by Alexander Hamilton and two other members of the Federalist party to write invective against Thomas Jefferson and his party.

You get the picture.

Nearly two centuries later the industry had its first major disruption. The daily newspaper was born, and suddenly regular people walking on the street or boarding their morning train could afford to buy an issue of whichever newspaper attracted their attention with no strings attached.

That last part is the key here. No strings attached. So, for the first time in history, news outlets had to compete for attention instead of writing for a captive audience.

“Special! Special! Read All About It!”.

And thus, the attention-grabbing headline was born. Of course they didn’t call it clickbait yet, but clickbait it was. Luckily, only one headline in the entire newspaper was loud and attention-grabbing; the rest could still be news. But the seed was sown, and the yellow press was born.

Half a century later, the New York Times managed to temporarily reverse the trend by introducing the subscription-only newspaper. And for a while, all was well, and news resembled news. But another half a century passed, and now the industry encountered a disruption that no business model could withstand – the internet.

It is hard to overstate how much of a revolution the internet was. Content was now free. Any reader had access to any written material. Copyright laws were a kafkaesque maze that no resource-constrained business could afford to enforce. And ads were the only sane option one could consider for monetizing his content.

And now, we arrive at the current moment.

The vast majority of content – news, opinion, hearsay, random musings – competes against all other content all the time. There is no “issue” or “paper” in which multiple items get packaged together. There’s only a giant bazaar of standalone offerings, all competing for eyeballs in the same way kids used to shout “Special! Special!” on every corner in the 1890s.

The world is producing enormous amounts of content. The subscription model has been relegated to the same small circles it served in the 1700s – educated elites and party loyalists. Everyone else consumes the news by clicking on the headline that shouts the loudest, and as they skim through the article without reading it too closely, they view ads. The ads pay:

a) per click, or

b) per view.

Now let’s pause. Remember how evolution works? You have a population of animals. A new selective pressure enters the environment let’s say all the low-hanging fruit is gone and the remaining fruit grows on tree-tops. What’s going to happen over time?

If you guessed “the average height of animals will increase” – you’re awesome; thanks for paying attention in biology class!

So, what happens to the population of articles if all the subscription revenue is gone, and the only revenue available is linearly dependent on clicks and views?

Now, don’t get me wrong, the good newspapers will still be better than the bad ones; there’s always a bell curve. But over the past 30 years, the whole curve shifted to the left. No one was spared.

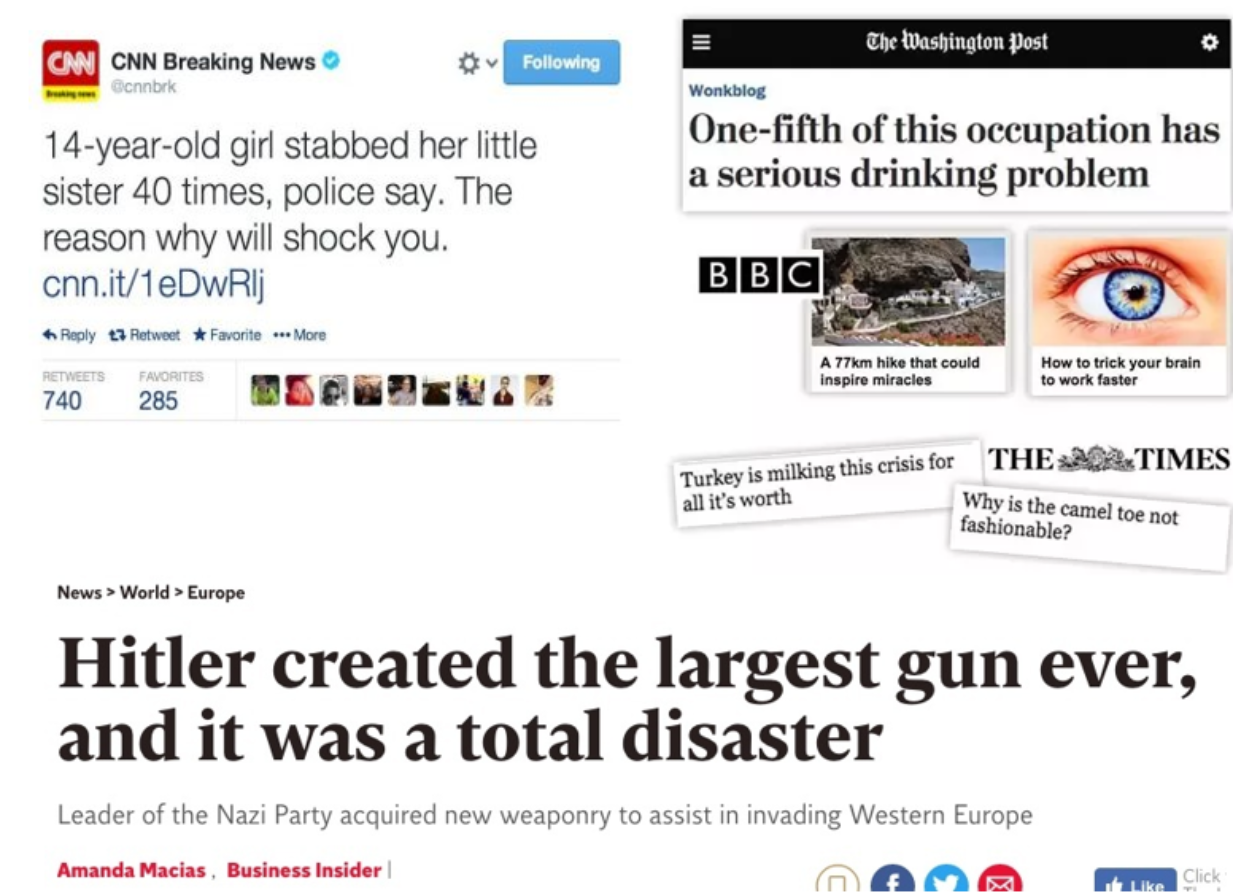

I’ll let CNN, BBC, WaPo, The Times and Business Insider do the talking for me here:

And thus, Chicken Little was right.

Now, you probably remember that I started this article by talking about how to fix the news, and so far, all we’ve done is talk about what broke it. It’s important though – you can’t fix things without understanding why they broke.

Moreover, once you understand why things broke, you can easily spot certain ideas that cannot possibly fix anything. For example:

1. Fact-checking.

Incentives to maximize clicks and views apply to every piece of content automatically; they’re built into the business model. Fact-checking is applied to a small subset of content, manually.

There is no way that manually checking a small subset of content can fix the universal incentive to produce attention-grabbing junk.

2. Organized efforts to fight misinformation or disinformation.

Junk is not misinformation. It’s also not disinformation. It’s just junk.

Any binary censorship rule that removes particular bad items from the entire population of junk will result in a slightly smaller population that – still – consists entirely of junk.

So, now that we’ve slaughtered the sacred cows, let’s consider what the parameters for a solution might be. We need something that: a) can be applied to all content in real-time, and b) creates an incentive to the publisher of the content to produce something other than junk.

Can you think of anything? Ok, let me give you a hint. The way you avoid sugar in your diet is by looking at the packaging of each food item and seeing a little label that says how much sugar this product has.

Wouldn’t it be useful if articles had packaging that did this too?

You’ll object, of course, that publishers have no incentive to place nutrition labels on their own content. And it’s this objection that leads us to the eureka moment – we don’t need them to. We can do it ourselves with AI.

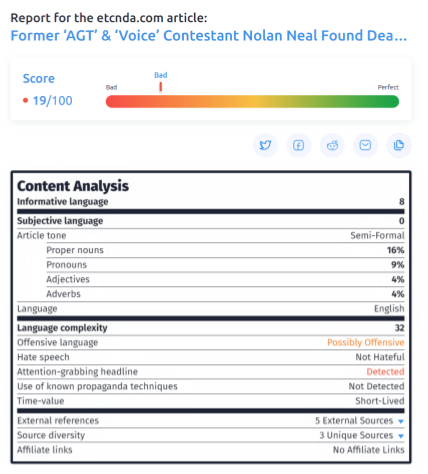

Let’s generate a nutrition label for every article, every podcast, and every video. Something like this:

And let’s consume all our content through reader apps and feeds that include this nutrition label with every piece of content. Better yet, let’s build reader apps that allow users to customize their feeds to specify which kind of articles they’d like to be included.

The result will be happier users of course, but more so – there will be a universal incentive to produce the kind of content that readers want to see. By collectively setting our filters to positions that reflect our long-term preferences (and not the things we happen to click on in the heat of the moment), we can gradually turn our preference for content that is not junk into something that has an actual dollar value.

And if we do, we can use AI to fix the news. Or die trying.

About the Author:

Alex Fink was born in the Soviet Union and raised in Israel. After traveling through 40 countries and living in Japan for a year, he settled in Silicon Valley and began a 15-year career as a tech executive in a variety of startups. Alex decided that instead of contributing to the problem created by Silicon Valley over the years, he would rather build the solution using their own methods. He moved to Austin, rolled up his sleeves, and a few years later the Otherweb was born. Otherweb’s mission is to improve the quality of information at every stage of its lifecycle – creation, distribution, consumption, and monetization. It views the quality of information that people consume as the most important input to people’s ability to make good decisions and act rationally.