ShotSpotter, when it was created, was meant to enhance policing and prosecution activities to reduce the rate of gun crimes in the communities that it was used. However, is this artificial intelligence (AI) failing to offer precise solutions?

Prosecutors in Chicago were forced to withdraw evidence generated by ShotSpotter, which resulted in police killing 13-year-old Adam Toledo earlier in the year.

In another incident that happened on May 31, 2020, 25-year-old Safarain Herring was confirmed to have been shot in the head and later dropped off at St. Benard Hospital in Chicago. The police said that Herring was shot by Michael Williams and he died about two days later.

64-year-old Williams was eventually arrested and charged with murder. Williams says that Herring was hit by a bullet from a drive-by shooting. A primary piece of evidence, in this case, is some video surveillance footage. The footage from the cameras show that Williams stopped his car on the 6300 block of South Stony Island Avenue at 11:46 p.m. That is the same time and location where Chicago Police say they believe Herring was shot.

How did the police know where the shooting happened? They said that ShotSpotter, which is a surveillance system that uses microphone sensors to determine the sound and location of gunshots, generated the alert for the place and time used in the prosecution of Williams.

But all that seems not to be entirely true based on recent court filings.

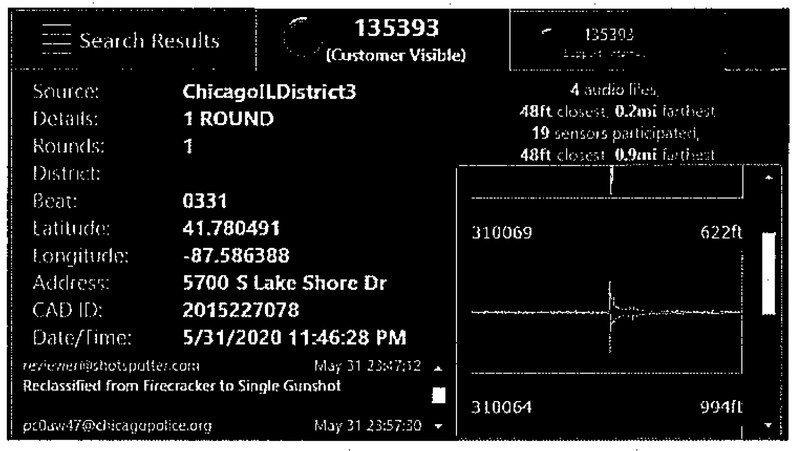

That fateful night, 19 ShotSpotter sensors recorded a percussive sound at 11:46 p.m. and triangulated the location to be 5700 South Lake Shore Drive. That location is just about a mile away from the place where prosecutors say Williams shot Herring, according to a motion filed by Williams’ public defender.

The firm’s algorithms originally classified the gunshot as a firework. During that weekend, there were widespread protests in Chicago in the wake of George Floyd’s murder, with some protestors lighting fireworks.

However, a ShotSpotter analyst manually overrode the algorithms after the 11:46 p.m. alert came in, and “reclassified” the resulting sound like a gunshot. Months later, another analyst changed the coordinates to a location on South Stony Island Drive near where Williams’ car was captured on the camera footage.

The public defender wrote in the motion presented in court:

“Through this human-involved method, the ShotSpotter output, in this case, was dramatically transformed from data that did not support criminal charges of any kind to data that now forms the centerpiece of the prosecution’s murder case against Mr. Williams.”

This document is referred to as a Frye motion. It is a request for the prevailing judge to examine and rule accordingly on whether a specific forensic strategy was scientifically authentic to be considered as evidence. The prosecutors withdrew all ShotSpotter evidence against Williams instead of defending the technology and its employees’ actions in a Frye hearing.

Analysts and experts say that this case is not an anomaly. The pattern that it represents may have massive ramifications for the artificial intelligence technology in Chicago, where ShotSpotter generates 21,000 alerts every year on average. Today, this technology is in use in over 100 cities.

Experts have reviewed a lot of court documents from the Williams case and many other trials in New York State and Chicago. The acquired data show that the firm’s analysts modify alerts often at the request of police departments. Some of the requests seem to be searching for compelling evidence supporting their narrative of what transpired in a certain case.

A Lot Of Untested Evidence From ShotSpotter

If Cook County State’s Attorney’s office did not withdraw the evidence against Williams, it would have become the first time a court in Illinois officially examined the source code and science behind ShotSpotter, according to Jonathan Manes. Manes is an attorney working at the MacArthur Justice Center. He said:

“Rather than defend the evidence, [prosecutors] just ran away from it. Right now, nobody outside of ShotSpotter has ever been able to look under the hood and audit this technology. We wouldn’t let forensic crime labs use a DNA test that hadn’t been vetted and audited.”

The senior vice president for marketing and product strategy at ShotSpotter, Sam Klepper, wrote in an email that the firm does not think that the prosecutor’s decision to withdraw the evidence reflects a lack of faith in its artificial intelligence technology.

Evidence and employee testimony from this technology has been admitted in at least 190 court cases. Klepper wrote:

“Whether ShotSpotter evidence is relevant to a case is a matter left to the discretion of a prosecutor and counsel for a defendant … ShotSpotter has no reason to believe that these decisions are based on a judgment about the ShotSpotter technology.”

Alteration Patterns

In 2016, in Rochester, New York, police were hunting for a suspicious vehicle. They stopped the wrong car and shot Silvon Simmons, in the back three times. According to the police, he was shot for firing first at officers.

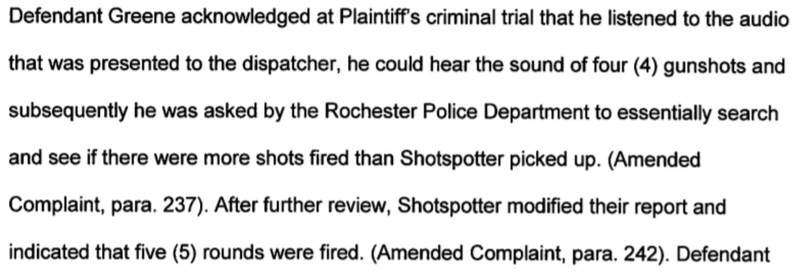

The only evidence that the police used came from ShotSpotter. The technology did not detect any gunshots initially and the algorithms determined that the sounds were produced by helicopter rotors. After the police contacted ShotSpotter on this issue, it ruled that there were four gunshots, the number of times Rochester police fired at Simmons, missing once.

ShotSpotter’s expert witness, Paul Greene, testified at the Simmons trial. The police asked Greene to look for more shots, according to a civil lawsuit Simmons has filed against the company and the city. Despite there being any physical evidence at the scene that Simmons fired, Greene came up with a fifth shot. Rochester police also refused to test Simmons’s hands and clothes for gunshot residue.

The ShotSpotter audio files that had the evidence of the fifth shot have since disappeared. According to Simmons’ civil suit:

“Both the company and the Rochester Police Department lost, deleted, and/or destroyed the spool and/or other information containing sounds pertaining to the officer-involved shooting. Greene acknowledged that employees of ShotSpotter and law enforcement agents with an audio editor can alter any audio file that’s not been locked or encrypted.”

Eventually, a jury acquitted Simmons of attempted murder. In that context, a judge went on to overturn his conviction for owning a gun, citing ShotSpotter’s unreliability.

In 2018, Greene was also involved in another changed report in Chicago, when 27-year-old Ernesto Godinez was charged with shooting a federal agent within the city. Evidence against Godinez included a ShotSpotter record which stated that seven shots were fired at the scene.

According to the platform, a total of five shots were fired from the vicinity of a doorway where video surveillance showed Godinez standing. Shell casings were later found near the doorway. However, video surveillance does not show any muzzle flashes from that doorway and the casings did not match the bullets that hit the agent, based on the court records.

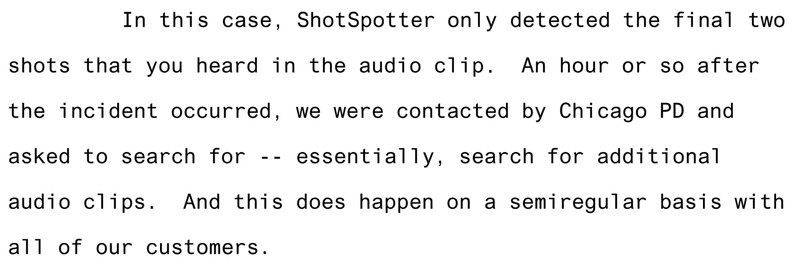

In the trial, Greene testified under cross-examination that the AI platform alert recorded two gunshots fired by another officer responding to the original shooting. Later, Greene re-analyzed the audio files after Chicago police contacted ShotSpotter. He told the court:

“An hour or so after the incident occurred, we were contacted by Chicago PD and asked to search for—essentially, search for additional audio clips. And this does happen on a semi-regular basis with all of our customers.”

Greene later said that five more gunshots were not captured by the company’s algorithms and acknowledged:

“we freely admit that anything and everything in the environment can affect location and detection accuracy.”

Klepper said that ShotSpotter analysts tend to agree with the machine classification more than 90% of the time. He explained:

“In a tiny number of cases, our customers request us to perform a location analysis to validate the accuracy of the location. If we find an error, we provide a more accurate location to the customer to assist the investigation.”

Before the trial, the judge ruled that Godinez should not contest Greene’s qualifications as an expert witness and ShotSpotter’s accuracy. Godinez appealed the conviction mainly due to the ruling. Gal Pissetzky, Godinez’s attorney, said:

“The reliability of their technology has never been challenged in court and nobody is doing anything about it. Chicago is paying millions of dollars for their technology and then, in a way, preventing anybody from challenging it.”

ShotSpotter Benefits And Shortcomings

This artificial intelligence platform comes with many benefits and shortcomings. It was initially designed to help the police to reduce gun violence and criminal activities wherever it is implemented. In some cases, it helped prosecutors unearth evidence that has helped convict criminals that would have escaped without its assistance.

But, at the core of ShotSpotter’s opposition is the lack of empirical evidence that it works. Its sensor accuracy and the system’s general effect on gun crime are yet to be analyzed. The firm is yet to allow independent analysis and testing of its algorithms. There is evidence that the allegations it makes in marketing materials about accuracy might not be wholly scientific.

ShotSpotter alleges that its system is nearly 97% accurate. But, Greene said that these numbers are not calculated by engineers. In 2017, he told a San Francisco court:

“Our guarantee was put together by our sales and marketing department, not our engineers. We need to give them [customers] a number … We have to tell them something. … It’s not perfect. The dot on the map is simply a starting point.”

The MacArthur Justice Center analyzed ShotSpotter data and discovered that in a 21-month period 89% of the alerts the company’s technology generated in Chicago led to no evidence of gun crime and 86% of alerts led to no evidence a crime was committed at all. Klepper disputed:

“The data source used to draw their conclusions, on its own, results in an incomplete picture of an incident because a gun may have been fired even if there is no documented police evidence that it was.”

“Greene’s testimony in the San Francisco trial had nothing to do with the determination of our actual historical accuracy rate. While marketing and sales have appropriate input on our service level guarantees for our contracts, actual accuracy rates are based on detections that we record.”

In the meantime, more research indicates that ShotSpotter has not helped reduce gun crimes in cities where it was deployed. Many users have dropped the company, citing a lack of return on investment and too many false alarms.

For now, the reports are mixed and it will take some more independent analysis of available data to determine the success rate of the artificial intelligence policing solution.